For years I

was a physician to members of his family and had known this 59-year-old

executive. I was surprised when he

was admitted to our hospital for palpitations and weakness.

I knew that he

used to drink alcohol socially, and when that became a problem, he had quit

sixteen years ago. I was aware

that he took pride in his health.

He was proud that he ate organic and natural foods. At admission we learned that he

consumed nearly a quart of yogurt each day, and also each day drank ten to

twenty cups of herbal teas.

His personal physician had seen him regularly for routine

health matters. He prescribed a medication

for anxiety. He had found that his

blood pressure was high, and it proved to be somewhat difficult to treat. Three

drugs were used in a step-wide fashion during the next 18 months.

Now, because of the

palpitations and weakness, he had gone to the emergency room of our hospital

where his serum potassium was found to be 2.2 millimoles per liter. Such low levels of potassium

(hypokalemia) are dangerous and can lead to ventricular fibrillation and death. He was admitted to the hospital for

close observation and treatment.

Potassium was administered intravenously and his serum

potassium level increased somewhat to 2.8 millmoles. His

palpitations disappeared.

His hypokalemia most certainly

was the cause of his symptoms, but what was causing his potassium to be so low?

As a thiazide had recently been added to his blood pressure

medications, the hospital’s clinicians briefly considered that this might be

the culprit. However, he was on an

appropriately low dose of the thiazide that ordinarily would not cause this

level of hypokalemia.

Over the next few days he remained markedly hypokalemic despite

additional potassium. Multiple physicians examined him

for other conditions that might cause hypokalemia, particularly those which

cause hypertension too.

Hyperaldosteronism was one such diagnostic

hypothesis. Although not common,

this can be a serious disease. Hyperaldosteronism

is the over production of a salt retaining hormone, aldosterone, which may

occur from an adrenal gland tumor or from severe narrowing of an artery to the

kidney, i.e., renovascular disease.

Other less common causes of hypokalemia and hypertension were also considered,

some of them seemingly benign, such as excessive amounts of licorice in the

diet, but the patient denied a fondness for licorice.

After extensive testing,

neither hyperaldosteronism nor any other cause was found. He was a diagnostic puzzle, but, he

felt well, and he was sent home when his potassium returned to normal.

Shortly

after discharge, at the request of his in-patient internist, he brought in his

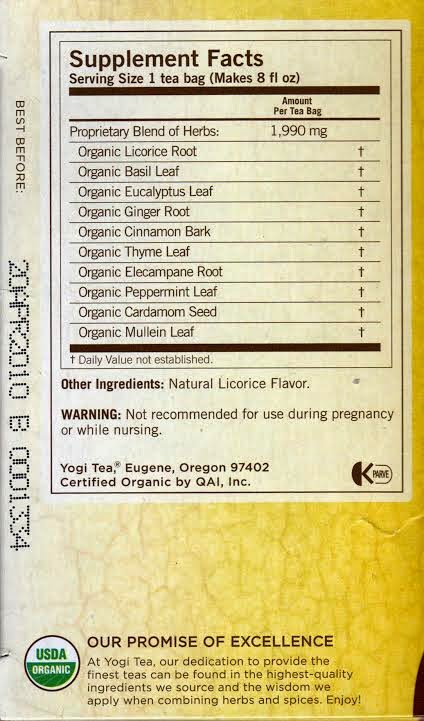

herbal teas. In each licorice root

was a major ingredient! The

mystery was solved.

As you

recall, he had mentioned at the time of his admission to the hospital that he

had been drinking ten to twenty cups of these teas per day for many

months. These were taken to

calm his nerves after tense days at the office. Even though they were intrigued

by the extraordinary amount of herbal teas that he drank each day, his

clinicians were unaware that some herbal teas contain licorice. He had denied licorice use.

He stopped

drinking the teas. He was seen

again in the clinic thirty days after discharge and he said he felt

terrific. His blood pressure was

104/64 and his serum potassium was 5.1 millimoles per liter. Antihypertensive medications were

reduced and eventually discontinued.

Eating

licorice is an uncommon cause of the syndrome of hypertension and hypokalemia. In

the past few decades with the virtual disappearance in the United State of

candy that contains true licorice root; it has virtually disappeared. However, it is important to note

that other sources of true licorice root are still available. These sources, including herbal teas,

should be considered in patients with unexplained hypertension and

hypokalemia.